The Sh’ma Project

A new dance film and educational initiative by Dr. Suki John

“Art cannot change events. But it can change people.” – Leonard Bernstein

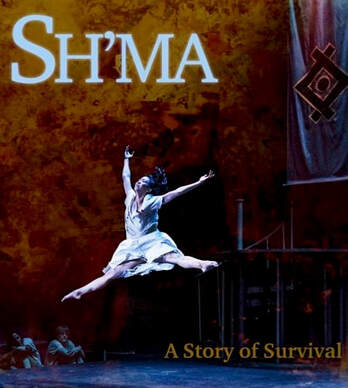

Sh’ma: A Story of Survival, a moving and innovative dance film, chronicles the journey of the director’s mother from school days to deportation, concentration camp to liberation, and finally immigration to the US. Sh’ma features a remarkable ensemble of 15 virtuoso performers, a haunting original score, stunning choreography, and timeless design.

Through the language of emotion, Sh’ma tells the story of one family’s experience in the Holocaust. Based on her mother’s harrowing journey from yellow star to deportation, concentration camp to refugee camp, stateless teen to American citizen, Suki originally choreographed Sh’ma in the former Yugoslavia. Not long afterwards, the horrific tragedy of the Bosnian war impelled Suki to tell her mother’s story again in New York, as new “Never Agains” reverberated across the globe. The ballet is being reimagined for the present moment, with an emphasis on reaching out to young viewers.

The film has been shown to invited audiences at the Museum of Jewish Heritage – a Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York City, and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas, where it was made. It has been nominated by 10 film festivals and awarded Best Experimental film by the New York Independent Cinema Awards. It was shown recently by the Miami Jewish Film Festival, and to a full house at the Santa Fe Jewish Film Festival. The filmmakers are currently exploring distribution and streaming options.

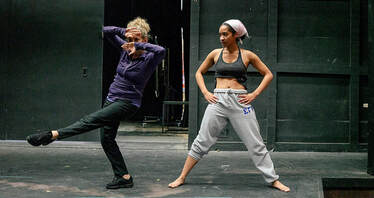

The Sh’ma Project is being designed as an artistic educational event. Suki will bring students and educators from Texas Christian University, professional dancers, and designers together with audiences across Texas. Special in-performance projections will help the viewers understand personal stories, historic context, and the action onstage. Student audiences will participate in pre and post-performance workshops, building a cohort to creatively address issues of antisemitism, exclusion, and othering.

In February The Sh’ma Project: Move Against Hate, will begin a pilot project in Texas high schools. It will introduce a shortened version of the film, Upstander Workshops and free educational materials as part of a three-part Holocaust and Human Rights arts and education initiative.

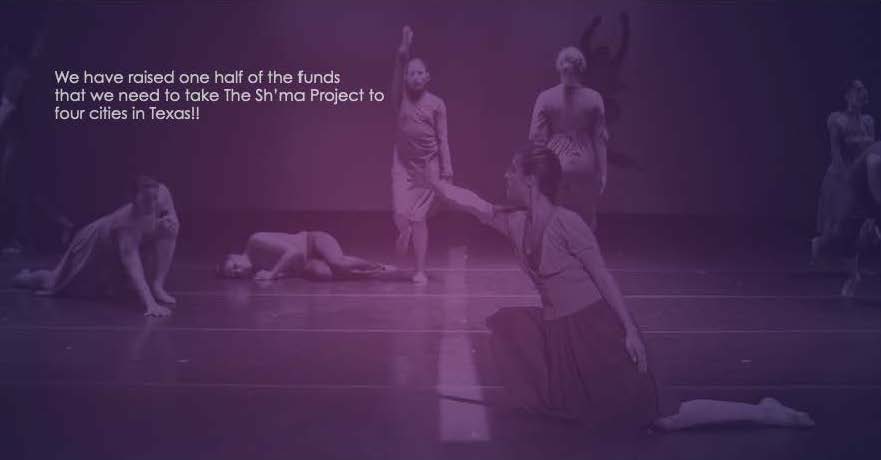

We need your help to make this happen with the best dancers, educators and designers we can find! Suki is trying to raise the funds to pay the dancers for their hard work. Please contact TJAA if you would like to support this effort.

The Sh’ma Project is more than an artistic educational project, it’s a movement against hate.

“The international resurgence of fascism and antisemitism spurred me to re-envision Sh’ma as a film. We took the iconography and costumes out of the past in order to create a ‘timeless’ look,” said Dr. Suki John. “The reasoning is that audiences—young people especially—will be less likely to dismiss the story as familiar old tropes, something that happened long ago and far away. It is my hope that they will allow the languages of emotion to affect them in ways that words cannot.”

More information, screeners, and interviews are available.

Please visit theshmaproject.com

For more info, contact Richard Laermer at richard@rlmpr.com.

IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO HELP MAKE THE SH’MA PROJECT FOR HOLOCAUST AND HUMAN RIGHTS ART AND EDUCATION HAPPEN IN TEXAS, PLEASE CONTACT US HERE: INFO@TEXASJEWISHARTS.ORG

Sh’ma: A Story of Survival

A captivating dance film by TJAA member Suki John

This film can be viewed ONLY from January 12-19, 2024 during a 48-hour window.

Click the link here to register to view the film at the upcoming Miami Jewish Film Festival. The cost is $11.25 to view the 66 minute file.

Sh’ma Film Preview Screening

Wednesday, September 27, 2023 6 pm to 7:30pm

View more details at the link here.

Dr. Suki John’s NBC5 Talk Street Interview

Dr. Suki John, TJAA Director of Dance and creator and choreographer of The Sh’ma Project, was recently interviewed by NBC 5 Talk Street. Check it out using the link here.

Sh’ma Film Screening

Private Red Carpet Event

March 5, 2023

6:00 PM

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

3200 Darnell St, Fort Worth, TX 76107

EVENT DETAILS

Lobby opens at 6:00 pm

Auditorium opens at 6:30 pm

Film begins at 7:00 pm

Q&A after screening

RESERVATION REQUIRED

A MOVING HISTORY EVOKING EMPATHY THROUGH DANCE ON FILM, SUKI JOHN SHARES HER FAMILY’S HOLOCAUST TRAUMA.

Article in TCU Endeavors Online Magazine, By Laura Samuel Meyn

During an early scene in Sh’ma, a choreodrama by Suki John, a teenage girl turns and leaps to ambient electronic music. While the spare set and atmospheric score imbue the work with a timeless feel, the story begins at a specific point in time and space: 1939 Hungary.

Warm moments between friends and family — a gathering in a nightclub, a candlelit Shabbat dinner — wither as fear takes root. As the government, following Nazi ideology, strips away the rights of Jewish people, the teenager’s parents argue; her mother thinks they should flee, while her father, a veteran of World War I who wants to continue his work as one of the country’s top radiologists, believes staying will be safe.

The work tells a true story, a personal one. The dancer portrays 14-year-old Veronka Polgar, the mother of Suki John, a professor in the School for Classical & Contemporary Dance at TCU.

Sh’ma means listen, a word in the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy. John’s work tells a searing family story with sweeping historical consequences. “I refer to it as the oldest story I know,” she said. “I don’t remember learning about this history. I just remember knowing it.”

Taking Shape

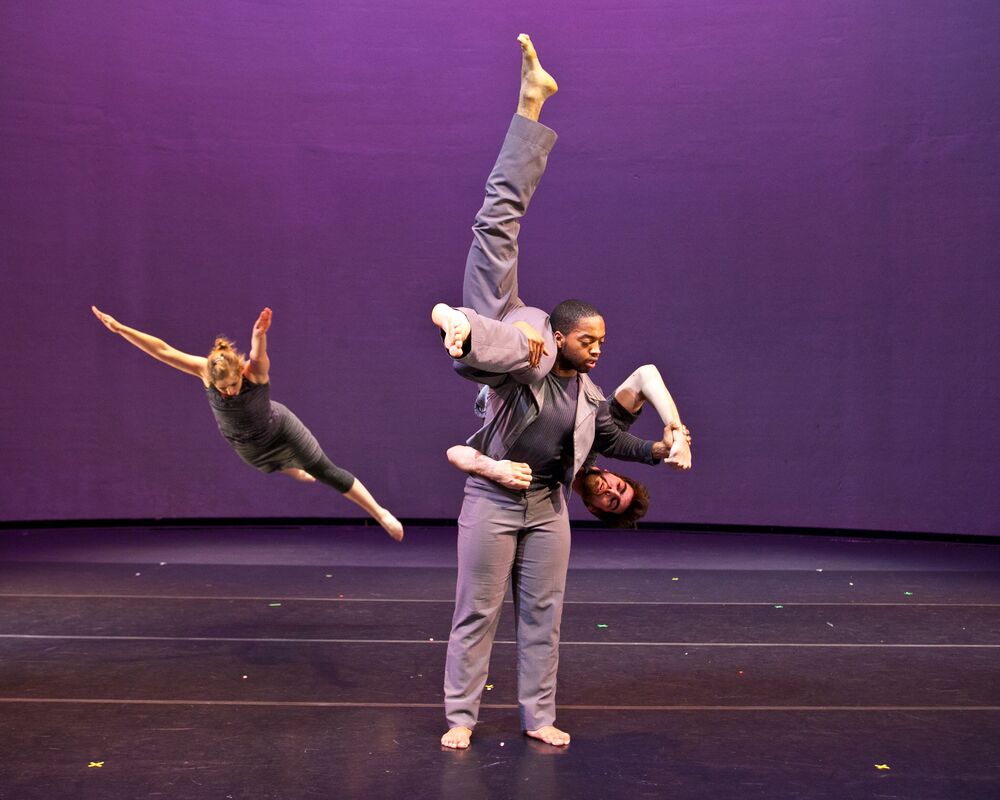

John recruited dancers from TCU and Texas Ballet Theater and hired three cinematographers to film Sh’ma, a work she first choreographed some 30 years ago.

Rivkah Cannon, an expert in Middle Eastern dance, designed the film costumes to feel timeless. “I wanted it to look like it could be happening now, or then, or possibly in the future,” John said.

Serbian composer Mitar “Suba” Subotić, known for his electronic music, scored Sh’ma in 1990.

The dance on film is the centerpiece of The Sh’ma Project: Move Against Hate, John’s human rights and educational initiative designed to teach audiences about the Holocaust.

The project includes workshops created with help from Lydia Mackay, professor of theatre. Offered before and after a screening of the film, the workshops invite audiences to prepare for what they’re going to see and set the stage for a response.

John enlisted her cousin Michael Polgar, a professor of sociology at Penn State Hazleton, to co-edit The Holocaust: Remembrance, Respect, Resilience, a free online textbook for the project.

In 2023, The Sh’ma Project: Move Against Hate will make appearances in high schools, universities, community centers and Jewish federations. “Because it’s in a film format,” John said, “it can go from Texas to Tel Aviv.”

FAMILY HISTORY

The project is personal for Polgar, too; his father, Steven, born Istvan, was Veronka’s brother. Through Holocaust studies and family conversations, Polgar has pieced together more of the story. Steven never spoke about the Holocaust, but Veronka and their mother, Sophie, did.

“They were forced out of Budapest, as were all Jews in Hungary,” he said, adding that most Hungarian Jews were sent to Auschwitz.

“Our family, because my grandfather was a well-known doctor, was among a small and select group of people who were sent to Bergen-Belsen,” Polgar said. “It was not a death camp; it was a concentration camp. Many people died there, but it wasn’t designed to do mass murder like Auschwitz.” Anne Frank, the same age as Veronka, died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen.

Polgar said that as the Nazis lost ground during World War II, they exchanged trains full of prisoners for resources. “On these trains — they were called Kasztner trains because they were organized by a controversial figure named [Rudolf] Kasztner — were basically ransomed refugees who were traded for trucks, medical supplies and, in the end, just money.”

Veronka and Steven Polgar’s aunt and uncle, who did not have children, gave up their spots on the first train in 1944, John said. The young Polgar siblings were thus able to ride to a home for refugees in Geneva.

“I don’t know my father’s weight when he was released, but they were sickly,” Polgar said. “My father had typhus. … They were emaciated, having been starved.”

Fearing they were orphans, Veronka and Steven Polgar nevertheless went to the train platform daily, hoping to find their parents. The happy reunion occurred four long months later, when a second Kasztner train brought more ransomed prisoners to Switzerland. Nazis and their collaborators murdered about 6 million Jewish people during the Holocaust; the Polgars were among fewer than 1,700 individuals to escape on a Kasztner train.

The Polgar family moved to the United States in 1948; the aunt and uncle who helped them also made it to America. But Veronka and Steven’s father, Ferenc, never recovered from the trauma of the Holocaust. He took his own life in 1949.

“It’s not just the trauma, it’s survivor guilt,” Polgar said. “People would kind of say … ‘Why didn’t they go to Auschwitz?’”

When Polgar and John were growing up as second-generation survivors, Polgar said the Holocaust wasn’t taught in their schools. “1978 was a watershed year because they showed a Holocaust miniseries on TV,” and the public was reawakened to the trauma, Polgar said. “We have almost a sacred obligation to tell the history.”

Polgar said that inviting Holocaust survivors to speak to his students has been more powerful than lecturing. “It’s not a history story. It’s not a war story. It’s a human story,” he said, “which is why works of art and testimonies are so important.”

The Evolution of Sh’ma

John first created Sh’ma for The People’s Theater of Yugoslavia in 1990. After she stopped by during a family trip to introduce her choreography with a VHS tape, theater directors hired her. One of the dancers didn’t want to perform the part of Veronka’s redheaded friend, whom a group of Nazis raped and murdered after she took off her yellow Star of David badge. Rather than remove the scene, John danced the role herself.

Sh’ma was well received and went on tour in Macedonia, but the company dissolved as the Bosnian war erupted. The conflict reflected Sh’ma in jarring ways, John said. “We know what happened in Bosnia, where rape was used as a weapon of war.”

John returned to New York, where she met Keith Saunders, a dancer and ballet master with Dance Theatre of Harlem, in a physical therapy office. Nearly a decade after she first choreographed Sh’ma, John produced it again, this time in Manhattan, with Saunders’ help. Artistically, it was a success; financially, John struggled to pay the dancers.

“I couldn’t get the press to cover it,” she said. “I actually had a New York Times journalist say to me, ‘I’m tired of the Holocaust.’ ”

In New York, Veronka was able to see her daughter’s work in person. “She was extremely proud of me,” John said. “I think it was harder for my father to watch. … Thirty-nine members of his family died in rural Hungary.”

John left the East Coast to join the faculty of TCU in 2007. Saunders joined her as a professor of professional practice in 2018.

In Fort Worth, John continued to choreograph; her works included pieces focused on social justice topics like disarmament and climate change. She also taught the Art and Activism class for the John V. Roach Honors College.

But Sh’ma stayed with her.

“The targeting of people based on identity, ethnicity, political or sexual persuasion is not something that has disappeared,” John said.

“The piece feels as relevant as it ever has, unfortunately. I knew I wanted to do it again.”

She spent four years securing funding. John said the first Texas organization to encourage and support Sh’ma was the Texas Jewish Arts Association, where she serves on the board as director of the dance division.

“Individual donors with Jewish Federation really pushed the project into existence,” John said. A TCU Invests in Scholarship grant provided seed money to begin the project; two diversity, equity and inclusion grants from the College of Fine Arts paid for pre-production; and grants from the college also covered use of studio and performance spaces. The project was also funded by the Zale Foundation, Anna Sosenko Assist Trust, Texas Women for the Arts/Texas Cultural Trust and Arts Fort Worth.

“This Sh’ma project — I speak of it as Suki’s magnum opus,” Saunders said. “She has been working this material, telling this story, for upwards of 30 years.”

Sh’ma on Film

To prepare for the lead role of Veronka Polgar in the film, Kira Daniel, a senior modern dance major, pored over Veronka’s journal and read Elie Wiesel’s Night, a haunting Holocaust memoir.

“Every scene that we work on, as soon as I go home and read the book, it’s literally the exact same; it’s just so real and raw,” Daniel said. “Every day, I feel like I’m closer to doing justice to her mother.”

Saunders portrayed Veronka and Steven’s father, Ferenc. In a heartbreaking moment that shows the dehumanizing impact of trauma, Ferenc, starving in a concentration camp, steals bread from his son. “It’s maybe that moment that I realized the full weight of it,” Saunders said.

In creating Sh’ma, John said she felt some release of the intergenerational trauma passed down to descendants of survivors. She experienced frequent war dreams until 1990. “After I made one of the hardest scenes in the ballet, the war dreams went away.”

Revising the work for film brought more release. She added a moment to Sh’ma where shoes are piled on stage; a Holocaust museum in Jerusalem inspired the scene. “I just felt all those shoeless souls around me and started having chills,” she said. “The dancers came and hugged me. It was beautiful to acknowledge.”

Daniel said performing in Sh’ma deepened her perspective on her chosen career. “Dance is just so much bigger than me going into a studio, learning a couple of moves and performing in front of people,” she said. “It can heal. It can bring communities together, give people hope.”

“Dance evokes kinesthetic empathy,” John said. “When you watch someone do something with their body, you feel it in your own body … in the kishkas — it gets you in the guts.”

OUR SH’MA TEXAS JEWISH POST ARTICLE IS NOW ONLINE. PLEASE SHARE!

HTTPS://TJPNEWS.COM/DANCE-PRESENTATION-ON-HOLOCAUST-MOVES-TO-FILM/

Never Again by Suki John

“How can there be art after the Holocaust?” asked my mother, who survived Bergen-Belsen. Then she asked, “How can life be worth living if there is no art, if life becomes only about survival?” As a second generation survivor, or child of the Holocaust, these questions have shaped my trajectory as a person and an artist. My mother’s story was the oldest story I knew, and I tried to make sense of it, and to understand how dancing could be meaningful, until finally I was given the chance to tell her story. I often wondered how to make sense of my own career choice to be a dancer and an artist. How could I do something that mattered in a world that was so full of injustice. These are questions I have thought about and struggled with and worked with over the years. When I was a young dancer my mother and grandmother took me to see the Green Table, the seminal anti-war ballet. It was created by German choreographer Kurt Joos between the world wars; he subsequently was targeted by the Nazis and escaped from Germany to England. The GT was danced around the world and my mother and her mother had seen it in Europe and been deeply affected by it. They felt it was essential that I see it and they introduced me to it with great seriousness and reverence, and when I saw it as a young dancer studying ballet at the Joffrey, it became my North Star. I understood what I wanted to do with my art and my legacy.

It’s a heavy legacy to have, and I struggled with how something as “frivolous” as dance could possibly hold that weight in a world where what happened to my mother was possible. How can we, as Jewish artists, speak to the existential chasm that is our heritage, without seeming maudlin or worse, opportunistic?

When I was in my early 30’s I was given the opportunity to create a work of my choosing in the former Yugoslavia. I was invited to a multi-national, multi-ethnic, multi-faith theater in Serbia, where I was given resources that were unprecedented to me: access to a ballet company, a composer, a theater company and a full complement of accomplished designers. After first meeting the theater directors in Subotica I was on the train back to Budapest, which was my family’s home before the war, I realized there was only one story I could tell in that part of the world. The story of my family’s experience, how they were deported from that home while their neighbors looked on. I had a deeply creative four months working with Macedonians, Serbs, Bosians, and Croatians on an evening-length choreodrama, or narrative ballet, I titled Sh’ma. “Why would anyone want to see that?” asked my brother, who knew our family story better than I. I responded by girding myself with history, poetry, novels and memoirs. But some things can be best expressed through what my mother called the language of emotion: dance. My grandparents came alive on that stage, and I stood in the wings feeling the relief of afterbirth.

I was the only Jew, or I thought I was, until opening night when my physical therapist – who’d been helping me for weeks – came up to me and very quietly told me that he, too, was a Jew and thanked me for telling the story of “our people.” Of course most of the Jews in that part of the world had been driven out or exterminated. In fact, the beautiful abandoned synagogue in the town of Subotica was used as a theater, which was not the worst use I could think of. I had prepared myself for encountering antisemitism before this journey, however I did not experience it. Instead, I experienced an almost eerie lack of semitism. I had ridden the train three hours and cross back into Hungary in order to find a cantor who could record the Sh’ma for my score. My second cousin accompanied me to the great Budapest synagogue, but got angry when I asked why she didn’t embrace that part of her heritage. She had adapted to her upbringing in post-war Hungary under Soviet rule, and she scolded me for never being able to understand because I had grown up in a democracy. I didn’t realize how scary it must have been for her and how stubbornly hate persisted, mutating in the shadows. Of course today that hate is out of the shadows, and what was shocking a few years ago is now not even surprising.

But I experienced my time in Central Europe as transformative. The process of creating Sh’ma freed me in many ways. For as long as I could remember I had had war dreams. While working on the ballet I had the last nightmare I would have for years. It was after I staged the rape scene, based on someone my mother called the Red Headed girl, who had refused to wear her yellow star. My mother alluded vaguely to what might have happened to her defiant friend before she was “shot into the Danube.” While I was trying to create the scene, the company dancers mutinied; they felt it was too graphic, and they refused to do it. The director of the company came to my defense, and claimed that one rape was not enough. She said that 100 rapes would not be enough to represent the horrors inflicted on women in war, and they should do the scene the way I directed it. Of course she was prescient. In a few years the Serbians themselves would use rape as a weapon of war in Bosnia.

Telling my mother’s story freed me. It freed me to go on to other subjects, to dance about joy and love and irony, to release the dead weight of responsibility. And yet. When the Bosnian war began to rage, I heard from the ballet’s brilliant Serbian set designer, Bojana Ristic. “It’s happening again,” she cried over a scratchy long distance call, “the story we told is happening here, now, again.” Within the context of the Bosnian War, and then the Rwandan genocide, there was no escape. A few years after dancing this story in Yugoslavia, there was no Yugoslavia left. So I told the story in New York, using the Holocaust as a metaphor for new “Never Agains” taking place around the world. Building on the sole support of a rehearsal grant from the 92nd Street Y, long a home for Jewish dance and dancers, I cobbled together a group of excellent dancers. All the while we did what dancers do: fundraising, going into debt, looking for performance space and press coverage. One Orthodox dancer requested a counterpart to dance her role on Shabbat, and special costumes to cover her knees and shoulders. But her parents wouldn’t watch her dance our history, because Orthodox women are not permitted to dance on the stage. The city beat writer at the New York Times said, “I’m tired of the Holocaust.” We all are. And yet, we told the story again.

History’s similarities reverberate in our bones. “Never again,” we say. But this story keeps insinuating itself, coming up in the international zeitgeist, and coming up in my personal worldview. Some of you know I recently lost my mother. She taught me to dance czardas around the living room, and we danced it on her last birthday when she turned 87. She looked for joy in a life she never took for granted. But last fall, at the end of her life, she talked about how she lay awake in her comfortable bed in Santa Fe, remembering her fear as a child, waiting for the Nazis to knock on the door. She said she couldn’t stop thinking about her immigrant neighbors, about children in her city waiting for the knock on the door, about them wondering if they would be deported, or separated from their parents, as she had been. And I think about how the story of my family is reflected in what is happening again and again. If I say I’m trying to dance “never again” we know it has happened again. Bosnia, Rwanda, Burundi, the Rohinga, whether it’s called genocide or ethnic cleansing, it keeps happening.

“Art can not change events,” said Leonard Bernstein, “but it can change people.” So I hold onto that idea, and I try to embody the truth of my experience, because sometimes the body can be more articulate than words. Having left the oldest story I know behind, I think I must tell it again, this time while living in Texas, surrounded by Confederate flags and immigrant detention centers. “All Jewish choreographers have a Holocaust ballet,” one of my colleagues says dismissively. Maybe that is as it should be, since the language of emotion reaches in and grabs us by the kishkes. What is our responsibility as artists in a world that does not value art, much less dance, in a world where the lessons of the past go unlearned? This time I will tell the story as I always imagined it should be told: with dancers in hijab and war-bonnets, dashikis and burkas, turbans and yarmulkes. Because we are all immigrants, we are all refugees, we all have a story to tell. And it is my hope that while we may not be able to change events with our art, we may be able to change people.

– Suki John

TJAA WILL BE HELPING RAISE FUNDS FOR THE SH’MA PROJECT

AND PERFORMANCES SCHEDULED FOR 2022. IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO HELP MAKE THE SH’MA PROJECT FOR HOLOCAUST AND HUMAN RIGHTS ART AND EDUCATION HAPPEN IN TEXAS, PLEASE DONATE HERE.

© Copyright texas jewish arts association 2024 | EIN #47-1191927 | all rights reserved | legal | site credit